September 17, 2011

How It’s Made: Incubate

This post is a long one, but I promise that the full recording is at the end…

I used to have a mild fascination with the show “How It’s Made.” The theme song, the background music, and the completely useless explanation of How things are Made. It’ll be a segment like “How It’s Made: Vacuum Cleaners,” and while the cheery music plays, the voiceover will say something like, “First, the frame is assembled. Next, a worker attaches the motor, which was assembled at another factory. Wires are connected, and the vacuum is complete! And that’s one vacuum that really… sucks!” (There’s always a bad pun at the end.)

Wait, wait – what the hell?! This isn’t “How it’s Made” so much as “How it’s Assembled.” I don’t think I have ever seen a single segment on the show that effectively explained how anything was made, top-to-bottom, except a segment I saw about pencils (the non-mechanical kind). The show, while charming, is useless. This blog entry will be the same, minus the charm.

I’ve been reading a lot of composer David Rakowski’s excellent blog lately. Somehow I didn’t discover it until last week, but I now read a post nightly. Rakowski lives in the Boston area, teaches at Brandeis, and has won just about every fancy composition prize. He wrote “Ten of a Kind” for the US Marine Band a few years ago, and it is possibly the most technically difficult band work I’ve ever heard. (Not positive, but I’m pretty sure it’s even harder than Steve Bryant’s Concerto for Wind Ensemble.) Rakowski’s music is heavily chromatic and sometimes thorny, but never to the point of bleepy-bloopy. It’s a harmonic language that I like a lot, as it’s a little outside of what I could ever actually do, and that makes it fun. Challenging without being incomprehensible is a wonderful balance.

At my request, Doctor Dave (that’s what I call him, behind his back) emailed me a few MIDI files of some of his piano etudes, so I could throw them at the new Disklavier. One of the etudes, “Wiggle Room,” is inspired by Bach’s Prelude in c minor from book 1 of one of The Well Tempered Clavier. If you don’t know that Bach prelude, here’s a recording of it, as sequenced (with a joystick, I might add) into my Commodore 64 when I was 13 years old. Prepare to be wowed.

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Bach-Prelude-Sidplayer.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

Being inspired by Bach, Rakowski’s etude goes so far as to contain no dynamics, articulations, or pedal markings, leaving those decisions up to the performer. (I can not imagine ever ceding that much control, unless I was allowed to restrict those performer-determined dynamics to a range between forte and fortississississississimo.) Here’s a video of my Disklavier performing the etude, with my own dynamics, articulations, and pedaling picked and added to the Finale file. (This was a lot of fun. Made me wish I could play an instrument in real time.)

Rakowski’s blog has some real gems. You should read “The Means Justifies the Ending.” First, though, you should read a personal favorite, called “Talk the Talk,” about the different ways that a composer needs to be able to talk about their music (to a concert audience, to a composition student, etc.). I was really struck by this paragraph:

Hard as it is to talk about music — it’s famously like dancing about architecture — talking about your own music is harder still. Not least because most of what a composer does — shut him/herself up in a small private place and spin out notes for private and convoluted reasons — isn’t really that interesting, except at the moment, to the composer. Moi-même, I probably find the act of writing pretty intense, since I almost never remember anything about actually writing it down — not even of writing Thickly Settled, finished just yesterday. I remember intentions and ways of thinking, but I completely forget everything about the actual act of writing it down. So how can I say anything intelligent about my own music if all I remember is intentions and not the actual act of composition?

I’m exactly the same way. Are there exceptions to this? Do composers ever remember the actual act of writing the notes? Maybe if the notes are pre-determined by some sort of system like a tone row, but if you’re working intensely on a piece and that work consists of intense decision after decision (see NY Times article about Decision Fatigue), selecting the notes and the rhythms and the dynamics for every moment, is there enough brain power left to remember those moments? In my experience (and apparently Rakowski’s), the answer is no.

It’s certainly true for my recently-completed percussion concerto, “Drum Music.” But let’s see if I can remember enough of the process for one movement – the second movement, “Incubate.” By looking at various versions of the piece, I can sort of remember a lot of it, even details like specific notes aren’t really there.

The initial idea: I wanted it to be extremely still. That would be unexpected in a percussion concerto, I thought. Could I also make it emotional? Could I make it sound almost haunted, but without using sound effects? Those were the questions I wanted to try to answer.

Okay, first thing’s first: it’s slow. But it’s part of a percussion concerto, so how would I accomplish sustained notes? First thought: rolled marimba. You can roll a marimba and sustain indefinitely, so that’s the best idea. But it’s not. It’s just the most obvious idea. Because we have to start somewhere, we’ll go with it.

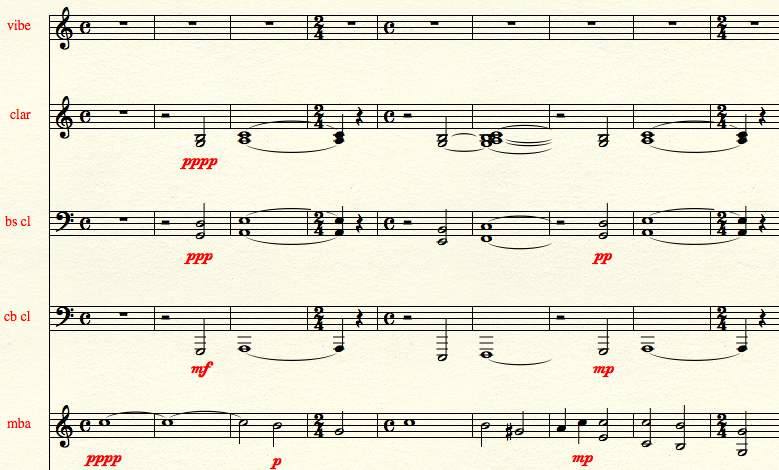

Okay, so we have rolled marimba. I got an idea for a very, very simple chord progression (this is me we’re talking about; I only know about 2 chords) – I have no memory of thinking of the progression itself – and I decided pretty quickly (based on what I entered into the first Finale file for the piece – there were 19 different files for this movement by the time I was done) that the progression would be in low clarinets.

There’s a sustained C in the marimba (bottom staff), not making it clear what key we’re in, and then the clarinets come in with a G major chord, making the marimba note a (mildly) dissonant note. The clarinets then move up a whole step (as any music theory class will tell you, don’t write parallel 5ths like you’ll see in the upper bass clarinet) to an A minor chord, and without doing anything, suddenly the marimba’s note is part of the ensemble’s chord. But then the marimba moves down a half-step to B, and it’s out of the chord again. Then it goes to G, also out of the chord, although these are very conservative dissonances. The marimba then begins to repeat those notes while the clarinet chords move down to a root-position E minor chord, then moving up stepwise to an F major chord – but with two notes from the E minor chord held through, resulting in an F major chord with an added 2nd and sharp 4 (the B natural – which also clashes with the marimba’s sustained C). While that chord is sustaining, the marimba changes a note from earlier, going to G# instead of G natural, which clashes pretty badly with the clarinets.

I say it clashes “badly,” but this is relative. If the accompaniment were not using all white-notes (that is, the white keys of a piano), but were more chromatic, the G# might not sound nearly as weird. As it is, though, it’s certainly noticeable that it doesn’t “fit,” but then it resolves to an A in the next bar, and we’re suddenly like, “wait, are we in A minor? I think we’re in A minor now.” (Even without perfect pitch – which I don’t have – when that G# resolves, it feels like it’s established a key of some kind. I think.)

Here’s what the above excerpt sounds like.

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Incubate-ex1.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

And I remember doing none of this. I can look at it and know why I did it, but I don’t know where it came from. One thing I do remember was that I really liked the chord progression. Pretty and simple. I liked it so much that I decided I would repeat it a bunch of times. If you repeat something a lot, it can be called minimalism, or repetitive, or annoying, or ostinato, or lazy, but since I was repeating a chord progression, I decided to consider it a passacaglia. That’s the fancy-pants term for a series of variations over a (mostly repeated) bass line or chord progression, frequently in a triple meter. Some argue that a repeated chord progression (rather than simply a bass line) is a chaconne, not a passacaglia. Since I eventually would vary the chords slightly while maintaining the bass line, I’ll call it a passacaglia. Also, this allows me to share an example of the most famous passacaglia, Bach’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor, also as sequenced by me into my Commodore 64 when I was 13 years old. If you thought the earlier prelude was impressive… (If you just listened to the MIDI excerpt above, you should turn your volume down. The Commodore is horrifically loud.)

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Passacaglia.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

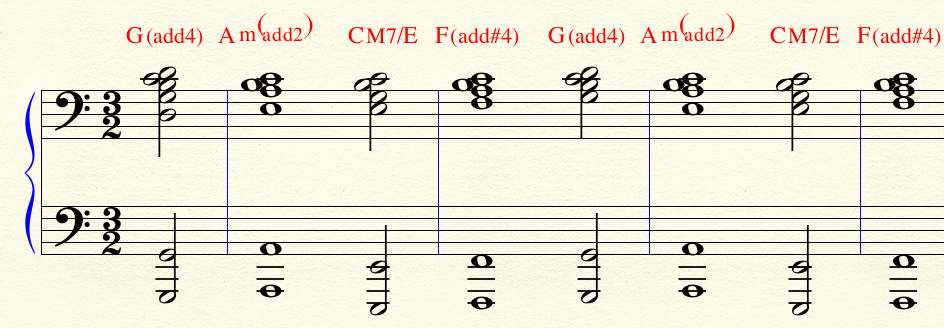

Bach’s progression is 8 bars long. Attention spans have dramatically declined over the past three hundred years, so my progression is two bars, consisting of 4 chords. (Note that it very quickly begins to simply repeat.) There is some variety over the course of the movement (sometimes the Cmaj7/E chord is just an E minor chord, for example), but this is the basic version.

Back to the solo percussion. I’d been writing this thinking it would be on rolled marimba. I wanted to also have bowed vibraphone at the same time, because, well, I love the color of bowed vibe.

Here was my first draft. You can see the bowed vibe above the marimba line.

It sounds like this:

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Incubate-ex2.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

Logistically, this was going to be very difficult. I thought it was reasonable to place a marimba and vibraphone in a way that you could play both at the same time (I’ve heard of this, although I’ve never seen it in person), but with the pedaling required of the vibraphone (if you don’t hold the pedal, the note stops immediately, the same as a piano whenever you release a key), and the reach of the marimba (the instrument is huge), this was going to be a nightmare. Okay, so what if we bowed the marimba instead? According to the Vienna Symphonic Library, if everything were on marimba – the mallet stuff and the bowed stuff – it would sound like this:

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Incubate-ex3.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

Very nice, but a much rounder sound, and I miss the color difference. Bowed vibe, especially with the pedal down, will taper off, but bowed marimba, particularly in this register, just kind of stops. And bowed vibe with the motor on is a great sound. (The vibraphone motor adds what is perceived as vibrato.)

So I kept playing around with the slow-motor vibraphone samples, and I didn’t want to give them up, but I couldn’t have bowed vibes and mallet marimba simultaneously. What if I gave up the marimba instead? Here’s the same excerpt with all vibraphone – one hand plays with two mallets, and the other hand bows the vibes as well.

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Incubate-ex4.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

This sounds to me like a haunted music box. This was the best one yet, and it fixed the issue of “how the hell does the same player play marimba with mallets and bow a vibraphone at the same time.” It also got me away from rolling the marimba constantly, which, frankly, gets pretty old rather fast.

Okay, so we’ve ditched the marimba for this movement, and we just have vibraphone. How should the movement start? (What you see above would eventually start at measure 15.) Because I was enjoying the slow-motor sound, and it’s easiest to hear that effect when it’s alone, let’s start it with a vibraphone solo. And to further embrace this whole “haunted” type thing we were doing, let’s put the pedal to the metal. In other words, we’ll ask that the player hold the pedal down the whole movement, creating a very wet sound, which when combined with the motor-created vibrato, would be exactly the sound I was after. The soloist will start the movement with a cadenza-like solo, in what feels like C minor, making the move to A minor (when the ensemble finally joins in) hopefully feel very satisfying. (I have no justification for why that would be satisfying, other than that I liked it, so that’s what it did.)

But just vibraphone? For the whole movement? That’s not super exciting. I wanted slow and still, but is there a way to make this visceral as well – and maybe visually theatrical? If the ensemble gets loud, we’ll never hear the vibraphone over it. But what would we hear over the ensemble, no matter how loud the passacaglia becomes?

Bass drum. I wanted to have a cadenza at the end of this movement that would lead to the beginning of the final movement, and I’d wanted that cadenza to start on bass drum anyway, so why not introduce the bass drum into the climax of this movement, during the slow, sustained passacaglia?

To summarize, the movement goes like this:

• Solo vibraphone plays an introduction with the slow motor and full pedal

• The ensemble enters with the passacaglia, a simple bass line of G, A, E, F, repeat

• On top of this, the vibraphone “teaches them a song” (to put it the way AEJ described it on first listening)

• The ensemble picks up the song (they’re quick learners), and they take over the melody while the soloist moves to the bass drum. Initially, the bass drum just sneaks in with some rumbling.

• The passacaglia gets bigger. Now it’s C, D, E, F, G, A, repeat. The introduction of the C chord – with all of the contra instruments playing the lowest C in the register – is a needed addition. It makes a big difference when the progression increases in size by 33%. (Insert inappropriate joke here. 33%? That’s nothin’!)

• The passacaglia repeats but continues up the range, so that on the next repeat, it’s an octave higher (starting on the next C). The bottom drops out, and we’re left with that last chord on A, but containing the notes A, B, C, D, E, F, and G (measure 52). This measure alone is the reason why there are 4 flutes and a piccolo in the concerto. Bass drum is no longer happy to be subtle.

• Twice more through the passacaglia, now loud and with the full ensemble, while the soloist plays the hell out of the bass drum – playing from the front of the stage, which should make for a fun visual. (I wanted this concerto to be fun to watch, too.)

• The passacaglia ends, and the soloist begins the improvised cadenza that will lead to movement three,

Incinerate.”

I realize a lot of this is not so much “how it’s made” as, “here’s what I made.” The rest of the details are a blur.

Here’s the link for the full score. “Incubate” begins on page 23. The audio (which is not on the main page for the work) is below.

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/PercCto-2.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

Comments

Larry Lawless says

Thank you for putting this up, John. What a great score study and thanks for the insight into "how you think"! I have only recently started keeping multiple Finale files of works in progress for the express purpose of going back and reviewing the process to remind myself, just what the heck was I thinking when I wrote THAT.

- Larry

Steven Bryant says

Great post! Funny, my Piano Concerto (which I just finished, btw), also has a repeated scalar passacaglia-ish bass (throughout first movement) - it must be in the air.

Chris Lexow says

John, it's amazing how you revolve around the idea that composers don't remember their writing. I feel that I'm the same way as well. I JUST finished writing a new piece yesterday, and i'm not entirely sure how I made some of the decisions that I did. Absolutely amazing.

On another note, fantastic writing with the concerto. The section that you present with the vibraphone and your decision to bow and play at the same time is terrific! I feel as though it has hints of Aurora Awakes in them as well ;-)

Fantastic Job!

Marc Bridon says

John, this score study has opened my eyes greatly to the concept of doubling instruments. Being fresh out of college, I didn't quite grasp just how drastically a sound can change with the addition or subtraction of an instrument. My ears weren't quite there yet.

I'll definitely be better attuned to timbre shifts thanks to this.

Sounds great!

Nicholas Hall says

This has been an amazing read about your percussion concerto second movement. I would love to see into your mind on some of your other pieces, maybe asphalt cocktail? (although that would be thinking a few years back).

The bowed and played vibes at the same time is genious, I'm jealous I never thought of that. Also for future referance, to play marimba and vibes at the same time you can put them in an L shape. (the low end of the vibes toughing the high end of the marimba) Depending on where the vibes are placed depends on how low you can reach on the marimba.

I'm very excited to hear a live recording of this work.

Nicolas Farmer says

Wow...

Nice climax! I am anxiously waiting for the live recording... this second movement is going to be the best part!

The first solo vibe part reminds me of exploring a haunted underwater shipwreck by yourself... good job at setting a mood!

NF

Alex Yoder says

I keep listening to this area at 0:28 in the Wiggle Room video - its blowing my freaking mind.

I really like that Incubate movement too. I wanna hear it live.

Andrew Hackard says

I really like reading process pieces from ANY creative folks, and this is among the better ones -- I learned a LOT just reading it.

I do have a question, though; how did you get the C=64 samples up? I've got some files I'd like to bring into the 21st century, but I don't have a computer to do it on.

Add comment